David I. came back from UAlbany Spring Break 2022 with a classic picture-book from his father’s childhood titled “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble” by William Steig. Incidentally, William Steig (yes, he was Jewish, not that this impacts the message or our ability to find one) is also the author of the book “Shrek” which inspired the very well-known movie of the same name. David I. brought the book up to UAlbany from New Milford NJ because he wanted us to come up with life messages (as we are wont to do – and perhaps one day to make a book from all of these messages in good children’s books) from this beloved family treasure published back in 1969 – this copy that David brought up is a first-edition!

David I. came back from UAlbany Spring Break 2022 with a classic picture-book from his father’s childhood titled “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble” by William Steig. Incidentally, William Steig (yes, he was Jewish, not that this impacts the message or our ability to find one) is also the author of the book “Shrek” which inspired the very well-known movie of the same name. David I. brought the book up to UAlbany from New Milford NJ because he wanted us to come up with life messages (as we are wont to do – and perhaps one day to make a book from all of these messages in good children’s books) from this beloved family treasure published back in 1969 – this copy that David brought up is a first-edition!

The book has an overall message(s), but also quite a few meaningful nuggets along the way – shared below in no particular order – and yes, many spoiler alerts!

THE ROLE OF MAGIC PEBBLES

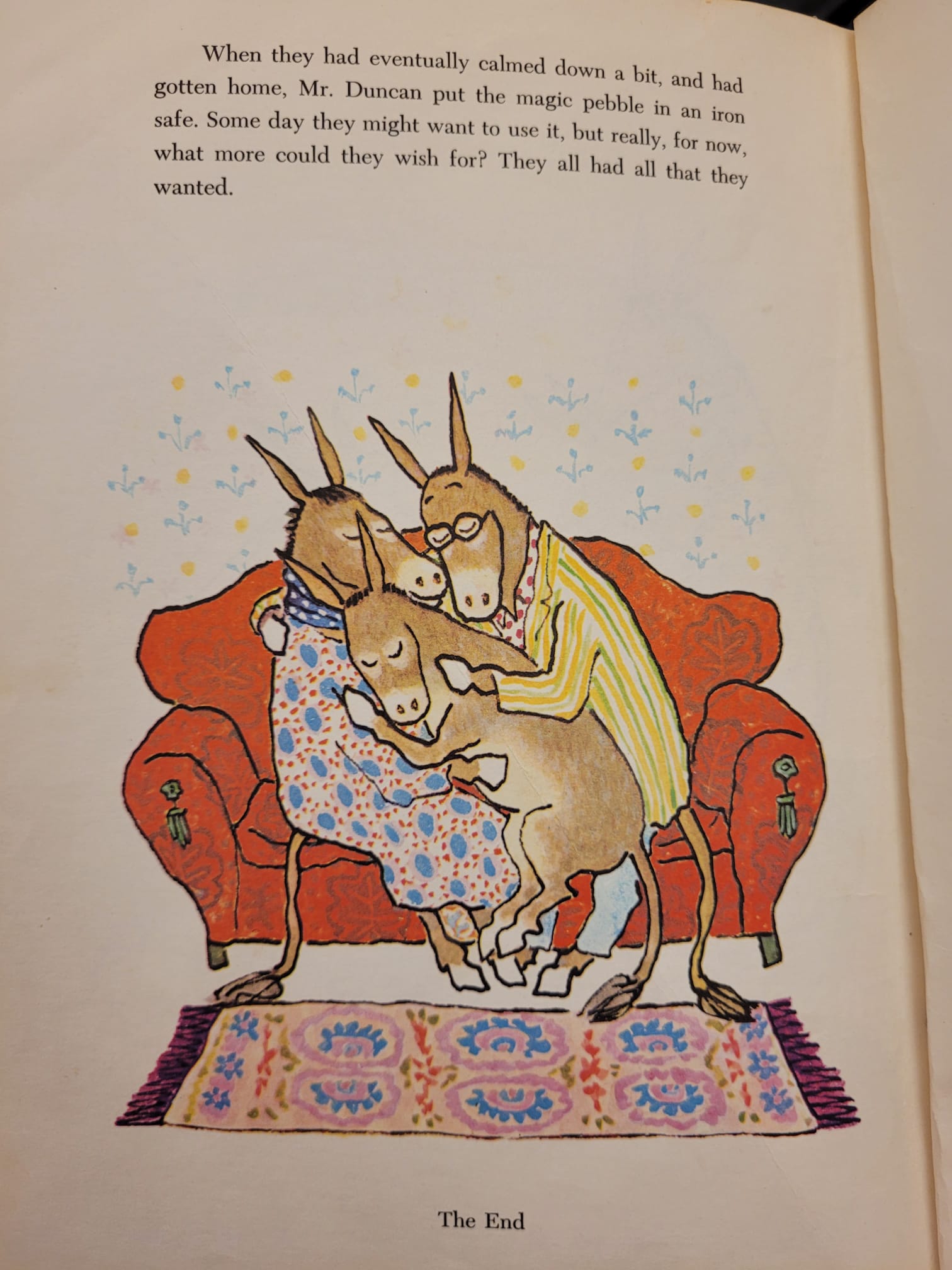

Perhaps the main point of the book is that instead of magical interference reaching for the unattainable, we ought to appreciate the simple pleasures and joys of life that we already have.

This is especially fitting for the Torah portion of the week that David I. brought this book up for: Shemini. In it we read of Aharon’s two sons Nadav and Avihu offering up a “foreign fire” to G-d and being consumed by it. Many commentaries (especially Chassidus Chabad) explain that they sought a dramatic spiritual high and ended up with a spiritual overdose. Of course, spirituality is wonderful ideal, may we all strive for more of it, but Chabad’s vision is to experience spirituality specifically within our physical life and world, to bring heaven down to earth, not to escape it. Sylvester was so enamored with the magical possibilities of the red magical pebble transforming his life, without realizing that the ultimate goal and ideal transformation is within our world itself, to see this within our regular lives – as indeed the last page tells us.

Interestingly, the last page of the book (which seems to hint at or allow for a sequel…) doesn’t tell us that they threw the pebble away or destroyed it for having nearly destroyed their lives. Instead, it tells us of how Sylvester’s father, Mr. Duncan, locked the pebble away in an iron safe, after all, “some day they may want to use it.”

Interestingly, the last page of the book (which seems to hint at or allow for a sequel…) doesn’t tell us that they threw the pebble away or destroyed it for having nearly destroyed their lives. Instead, it tells us of how Sylvester’s father, Mr. Duncan, locked the pebble away in an iron safe, after all, “some day they may want to use it.”

This teaches us that spiritual striving and spiritual ecstasy (that Nadav and Avihu sought) may indeed have their appropriate time and place in our Jewish experience, but not as the end all be all, it’s not the main approach. It’s meaningful and helpful within a broader use and context, but not as an end in itself.

But beyond the main message of the book, there’s an abundance of depth and relevance to so many of its parts and pages, we’ll try to get to a number of them, in no particular order (and not in the order of the book’s events):

WHO DOES THE WISHING?

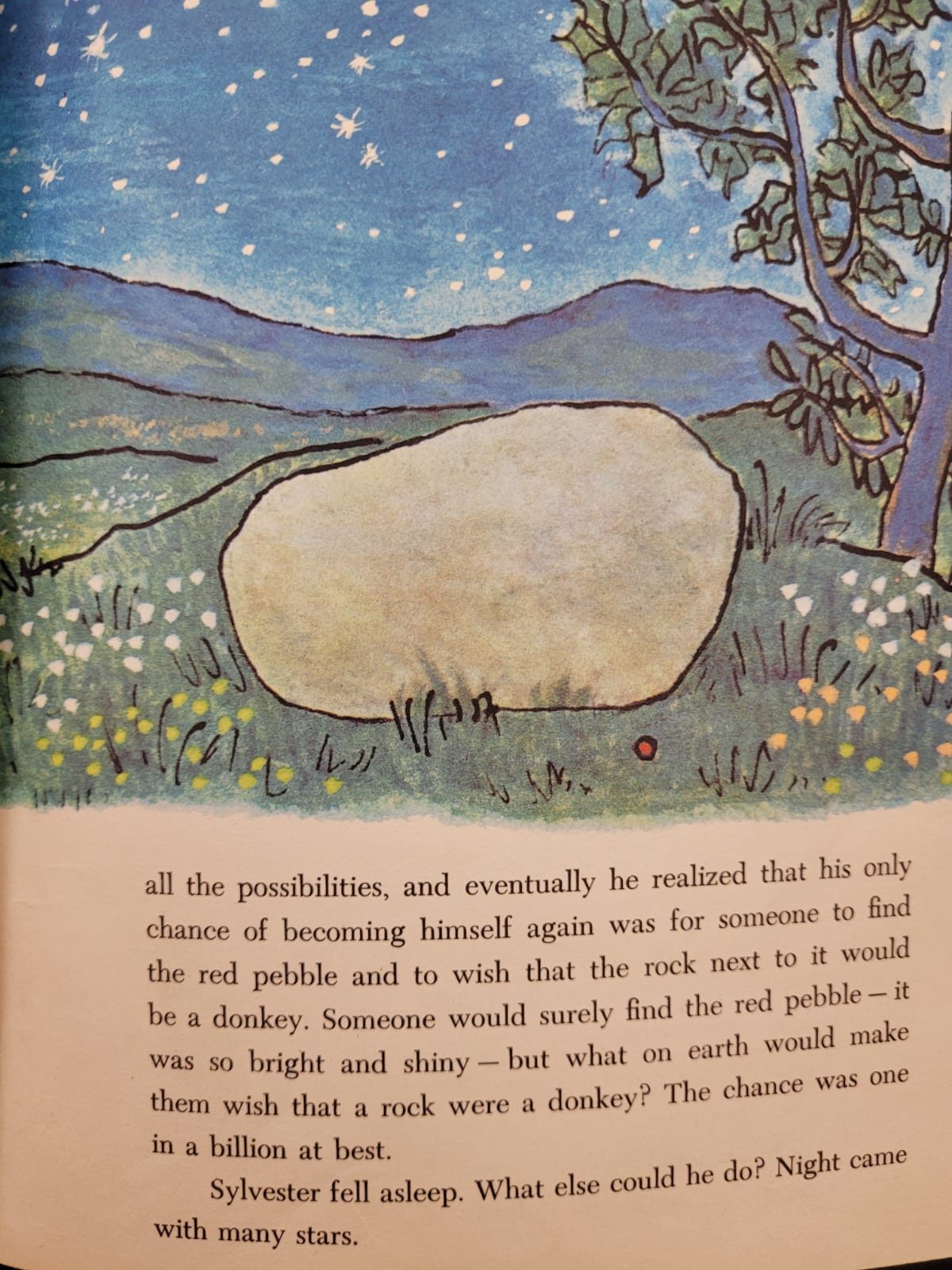

Amidst Sylvester’s worried thoughts sitting there as a rock was imagining the possibilities and calculating the odds (as he saw it, “one in a billion at best”) of someone coming along, finding the pebble (which in of itself he thought quite possible, as it was such a shiny red and noticeable pebble) and wishing while holding it that the rock next to it would turn into a donkey. Who could come up with such a thing!? It felt impossible.

Amidst Sylvester’s worried thoughts sitting there as a rock was imagining the possibilities and calculating the odds (as he saw it, “one in a billion at best”) of someone coming along, finding the pebble (which in of itself he thought quite possible, as it was such a shiny red and noticeable pebble) and wishing while holding it that the rock next to it would turn into a donkey. Who could come up with such a thing!? It felt impossible.

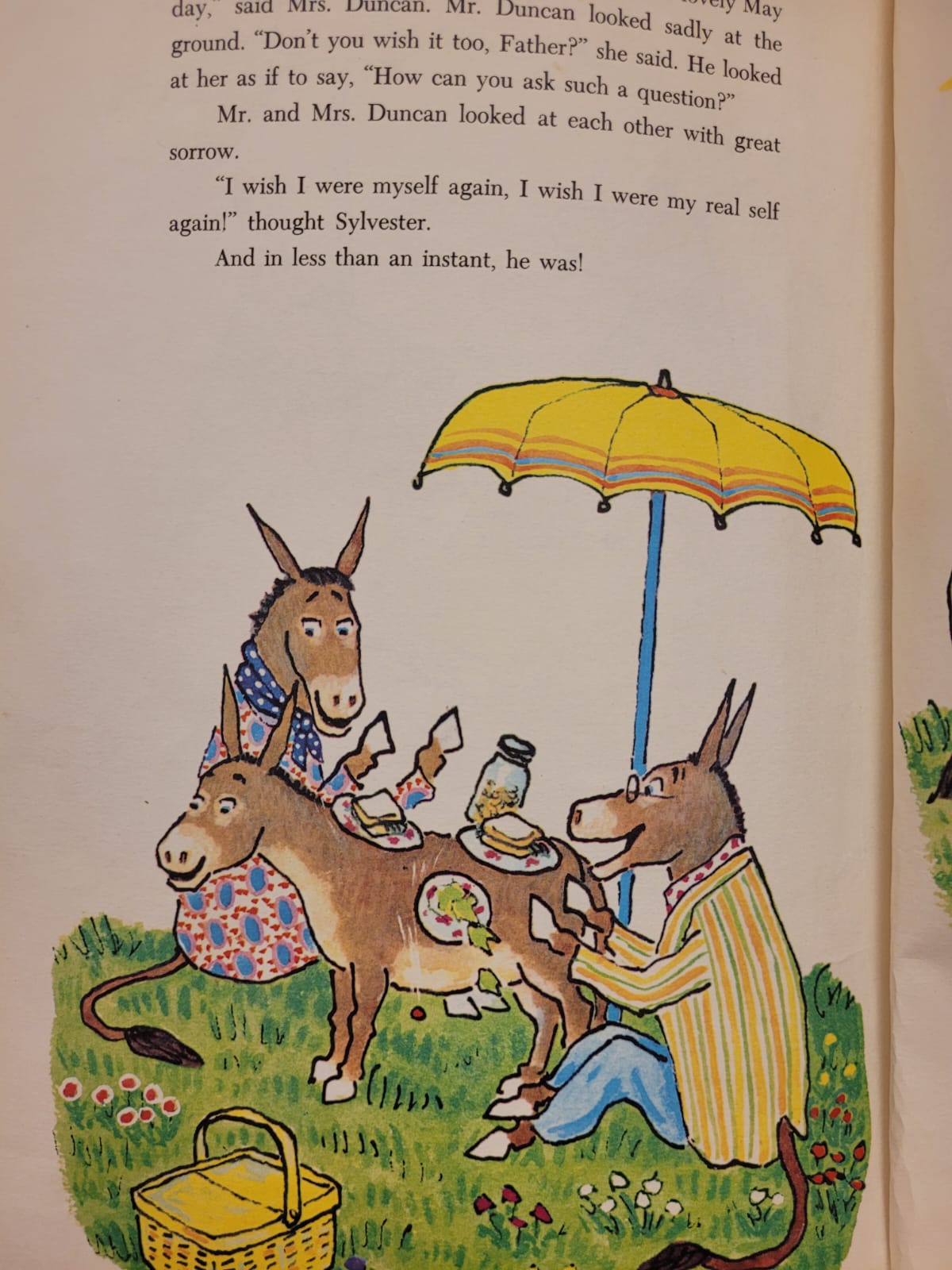

Little did Sylvester realize, even as he tried imagining and calculating all the possibilities, that if someone were to place to pebble atop the rock (himself for the time being) he could do the wishing himself! Indeed, the transformative change we seek, while it does require some outside assistance (such as someone placing the pebble on him) can be best achieved when we do the wishing ourselves! And in fact (or fiction, actually) that’s what happens at the end of the book – spoiler alert!

Too often people don’t realize their own empowerment, they rely too heavily on others as their only salvation. Another point pointed out by the book: Even when Mr. Duncan (Sylvester’s father) places the pebble atop the rock (unbeknownst to him, their son Sylvester!) Sylvester does not realize that this pebble is actually the magic pebble! We often don’t see the power that we have and therefore are little disposed or inclined to use it and make the most of it.

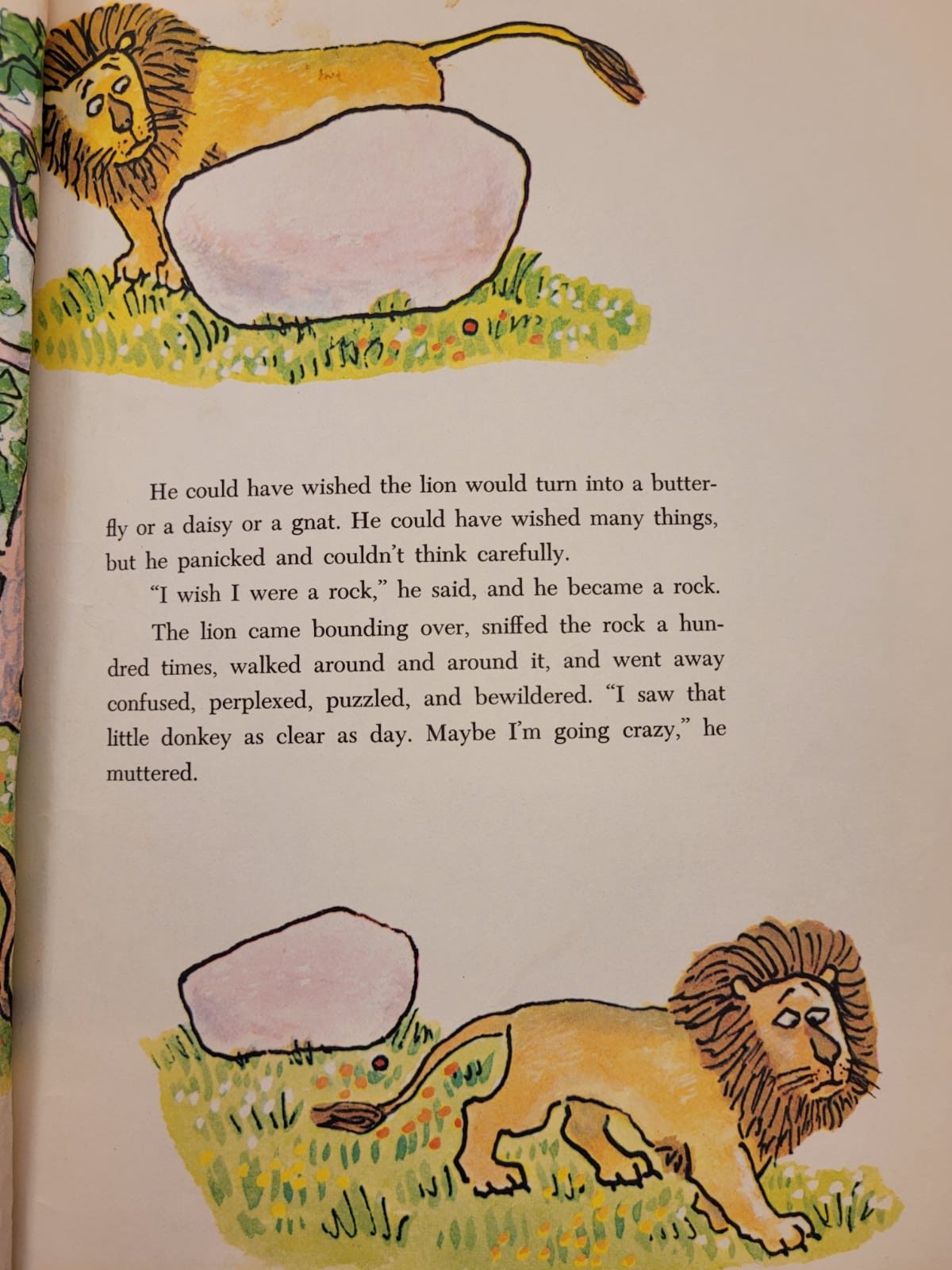

This is where Sylvester and the magic pebble story starts to get into some serious trouble. After finding the magic pebble and realizing its magical properties (as he does through the due scientific process of hypothesis and proof) Sylvester eagerly sets for him with it. But then, on Strawberry Hill, he encounters a mean, hungry lion (who like to eat young donkeys). The book describes the many wiser options Sylvester could have chosen had he been thinking clearly: for the lion to disappear, for him to get home safely, for the lion to turn into a goat or butterfly. But Sylvester wasn’t thinking clearly or carefully, because he panicked.

This speaks to the importance of the “Al Tirah” song we sing after each of the prayers (which the Rebbe greatly encouraged). The collection of verses comes from the Midrash on the Purim story, but the opening words “Al Tirah” mean: Do Not Fear! If you look up the Hebrew word fear in a Biblical Concordance (a book I often use for research) you’ll see that its one of the most oft-repeated words in the Torah, perhaps one of the phrases (in its various forms) that G-d says most of all to the Jewish people, from Abraham on down!

On another page in the book, where Sylvester is anxiously worried about his fate, it says an important line (of caution): “Being helpless, he felt hopeless”. Fear can be a great inhibitor. It can stifle or even paralyze us, it can drag us down. Or as in his encounter with the mean and hungry lion, it can keep us from thinking clearly and carefully. We did a Torah-Tuesday class once on why the Baal Shem Tov’s father’s dying words to him were: “Fear Nothing but G-d” especially for a person like the Baal Shem Tov whose entire life was devoted to love, but perhaps fearing nothing enabled him to innovate, to be boldly different, to go against the grain at the time. I find it very interesting that in Joseph Telushkin’s book “Rebbe” he devotes an entire chapter to the “Fearlessness” that the Rebbe instills within Chassidim, and the emboldening empowerment and horizon of possibilities and opportunities that comes with that.

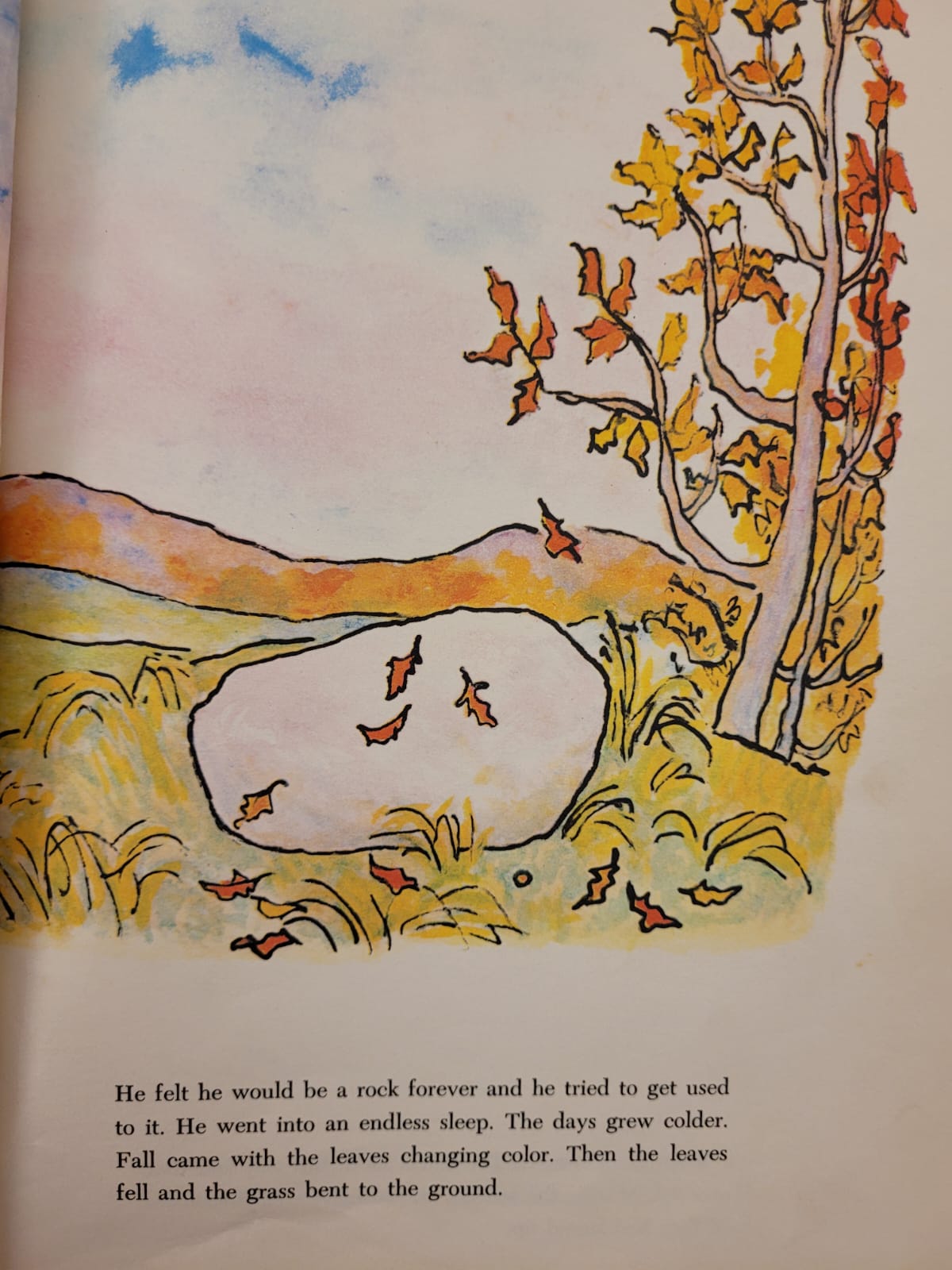

After months and changing seasons of being a rock and seeing no way out of it, Sylvester tried get used to it. He felt he had no options (indeed, he was locked into his situation until something would change) and was resigning himself to the situation.

There’s a visual Chassidic story about this: Once at a farbrengen long ago, it got very dark and the Chassidim were sitting in the darkness, or that someone had to go down to the cellar where it was extremely dark. A Chassid called out: “Not to worry, after a little while your eyes get used to it!” Reb Hillel Paritcher, a great Chassidic elder, used this as a learning opportunity, a message: “The biggest problem with ‘darkness’ (or exile) is when we get used to it, when we get comfortable there”.

Tanya speaks about the uphill constant struggle of the “Beinoni” (the average or normal Jew) and one of the frustrations being the continued, ongoing, everyday battle over the same issues, day after day, year after year. But getting used to it can mean throwing in the towel. We can’t get too comfortable, must continue to strive upwards. A pearl is created because the oyster is irritated by the grain of sand. If it stops being bothered by it, there goes the beauty of the pearl. Even when we can’t change our situation, we shouldn’t resign ourselves to it.

DEALING WITH GRIEF

I don’t have a picture of this page, but as months went by and Mr. and Mrs. Duncan (Sylvester’s parents) exhausted every avenue in their tireless search for their son (not going to comment on the social-commentary of what type of animals the police are depicted as) they tried to settle back into normal ordinary life best they could – but the problem is that ordinary life included their son Sylvester and they were reminded of him at every turn.

This is a profound understanding of grief and loss. It can be very hard, to move on, when moving on is back into everything that reminds you of that loved one. It also recalls the biblical story of Jacob pining for his lost son Joseph, refusing to be comforted.

There’s another insightful line in the book, where Mr. and Mrs. Duncan are picnicking at the rock (which was Sylvester). By the way, the fact that they went out for a picnic, as a way to help Mrs. Duncan deal with her sorrow is in itself enlightening. Mrs. Duncan turns to her husband and asks “Don’t you wish it?” (to see Sylvester again) and Mr. Duncan looks back at her worldlessly, as if to say, as the book says, “How can you even ask such a question?”

Some people need to verbally express and articulate their feelings, others tend to leave it unsaid. This may be a male-female thing, or it might not be, but in relationships it is important to understand various types of expressing feeling and communication, and what the other (spouse, friend etc) may need to hear.

—

It was fun reading this aloud with students and our kids after dinner on Friday Night, and sharing the “conclusions” and messages at Shabbat lunch. There’s depth to be found, lessons to be learned! There’s more we discussed and explored, but that’s it (for now) for this post. Thanks David for bringing up the (first edition!) book from home, still intact from your father’s (and his siblings) childhood, and for believing that we would come up with something meaningful…